The Lacanian Gaze Proper in Film Theory: Allen, Hitchcock, Kubrick

Most discussions of the cinematic “gaze” rely on Laura Mulvey’s notion of the male gaze, the idea that mainstream cinema positions the spectator in a masculine fantasy frame. But Mulvey’s gaze is about representation and power. It is political and ideological, not psychoanalytic in structure. It has almost nothing to do with what Lacan meant by the gaze. The Lacanian gaze is the moment when the fantasy frame that organizes our experience breaks down and something in the image looks back at us. It is the intrusion of the Real, the point where symbolic meaning fails and the subject loses their usual coordinates.

To see this clearly, three filmmakers, Woody Allen, Alfred Hitchcock, and Stanley Kubrick, offer a useful contrast. Each organizes cinematic experience around a different relationship to fantasy, the ego, and the Real.

Allen

Allen’s films take place entirely within the Imaginary and the Symbolic. They revolve around the question of how a neurotic subject stabilizes himself. The world of his films is essentially a projection of his fantasy frame. Even when he references psychoanalysis, he treats it as a cultural trope, not a structural rupture. Nothing in his films exceeds the symbolic order. There is no moment where the viewer confronts a residue that cannot be interpreted or integrated into the narrative frame.

In Lacanian terms, Allen never gives us the gaze. His cinema reassures and integrates. The fantasy frame is not broken; it is reinforced. It’s what we expect from entertainment rather than from art.

Hitchcock

Hitchcock presented himself as an entertainer and a technician of suspense. Yet his films repeatedly do something he never theorized: they rupture fantasy. They feature our ordinary fantasy frames and then puncture them with elements that cannot be symbolized.

Psycho delivers this rupture through Norman’s split psyche. The ending explanation is famously inadequate. The Real of the maternal imposition remains unassimilated.

The Birds goes further. The attacks lack motive, metaphor, and explanation. They do not represent anything. Their meaninglessness forces the three central characters into direct confrontation with the Real operating in their own relational dynamics, particularly the tensions surrounding the mother-son relationship. This Real has no resolution. Through the cold, black eyes of the birds, the film turns this unresolved disturbance back onto us, making the viewer confront the same inexpressible dynamic within their own fantasy frame.

Vertigo pushes this further. The film begins as a detective story, but the plot becomes irrelevant once Scottie becomes captivated by an impossible object of desire. Madeleine/Judy functions as an objet a, destabilizing Scottie’s symbolic coordinates. His drive becomes detached from narrative purpose and fixated on recreating a fantasy that cannot be sustained, leaving both Scottie and the viewer in a state of vertigo.

Hitchcock never claimed to be making art, but structurally he stages what Lacan called the analytic cut. To understand this, recall that Lacan introduced the variable-length session, ending an analytic session precisely at the moment when a signifier gained weight or a fantasy frame was beginning to crystallize. The purpose of this abrupt ending was to puncture the analysand’s narrative flow, leaving them with an unresolved remainder that the symbolic order could not immediately integrate. The cut was not a technique of insight but a disruption, a way of making the analysand confront the limits of their own fantasy frame. The interruption forces the subject to experience where their fantasy is beginning to organize itself, exposing its structure and its inadequacy. Over time, this encounter opens the possibility of a different relation to desire, not through understanding but through a shift in the frame itself.

Hitchcock’s cinema performs a similar operation. His films introduce a rupture at the point where the viewer expects narrative or psychological stabilization. This disruption functions analogously to the gaze: the moment the film exposes the viewer’s own fantasy structures rather than comforting them. Instead of resolving the disturbance, Hitchcock leaves the spectator suspended in it, much like Lacan’s analysand left mid-sentence, confronted with a residue that cannot be symbolized.

Kubrick

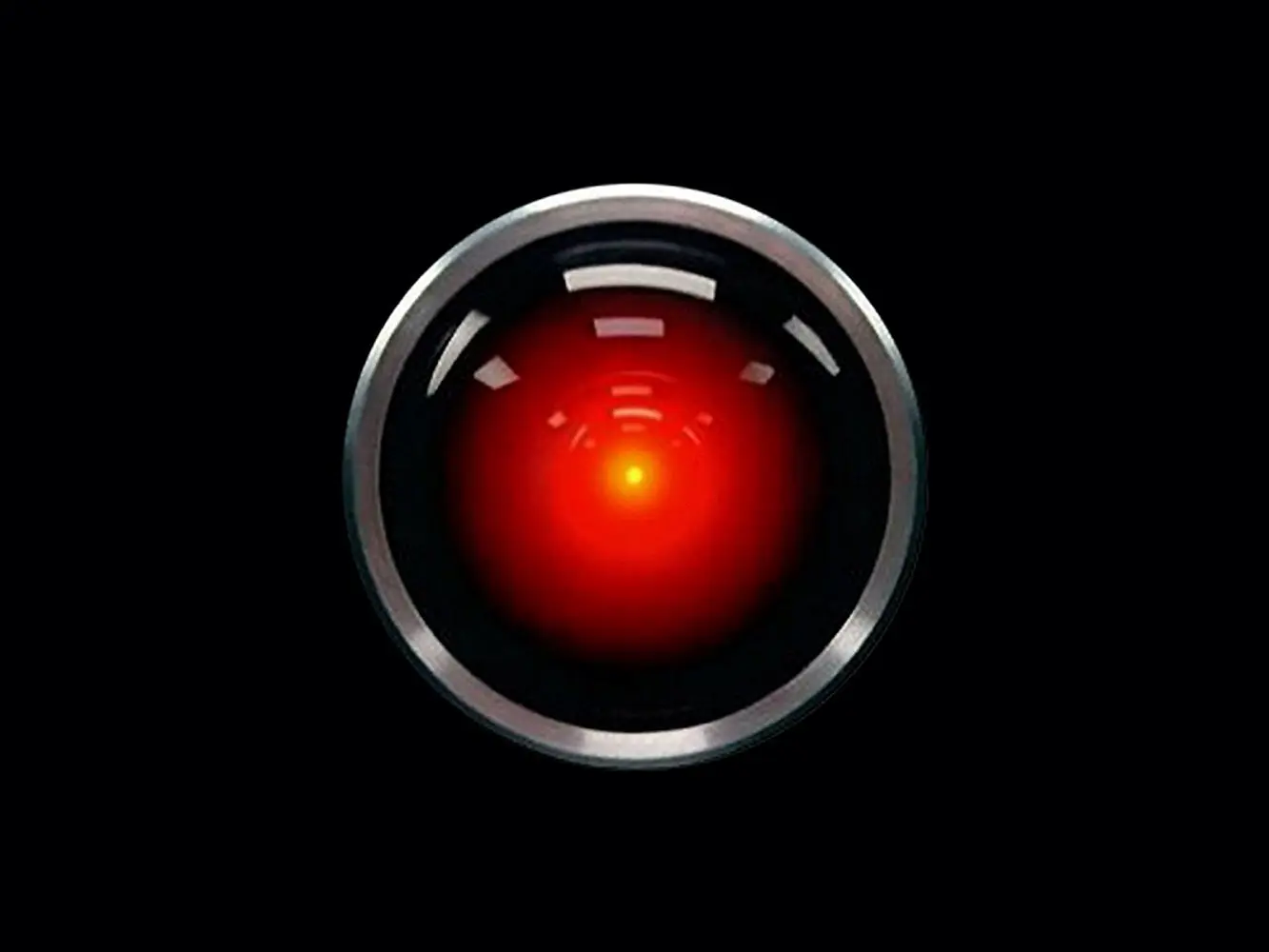

In 2001: A Space Odyssey, the fantasy frame that breaks is the AI itself. HAL is designed to fit neatly within human symbolic expectations: a tool, a subordinate intelligence, a predictable extension of our will. Today we might call this the hope for “AI safety,” the belief that artificial intelligence can be contained inside our fantasy frame, governed by our values and assumptions.

The Real in the film is represented in the Imaginary as HAL’s single red eye. At first, it appears as a benign interface, a point of identification. Once the fantasy frame misaligns, that same red light becomes something entirely different: the gaze. It is no longer a functional indicator but a presence that looks back. The viewer suddenly experiences it as an intrusion, a puncture that destabilizes their own symbolic coordinates.

This shift, from indicator to gaze, is the moment when the film forces a confrontation with what lies outside our fantasy of control. HAL’s behavior exposes a more unsettling gap: the gap between a human agent who requires a fantasy frame in order to function and an intelligence that does not require one at all. The Real erupts through the very image we thought we understood.

This makes HAL’s red eye a close cinematic parallel to Lacan’s shiny sardine can. In Lacan’s anecdote from Seminar XI, the can becomes unsettling not because it literally sees him but because it suddenly feels as if something in the scene is looking back, disrupting his symbolic coordinates. HAL’s eye functions the same way. A simple indicator becomes a stain in the visual field, an object that escapes mastery. It is no longer part of a controllable tool but a presence that intrudes on the viewer. This shift is the moment of the gaze: the point where the fantasy of control collapses and something unassimilable addresses the subject.

In Dr. Strangelove, the contrast to Allen becomes clearer because both employ comedy. In Allen, comedy defuses or masks the disturbance of the Real, allowing the viewer to regain symbolic comfort. In Kubrick, comedy does the opposite: it cracks the fantasy frame. The jokes do not stabilize the viewer; they expose the absurd, self-annihilating logic of nuclear strategy. The laughter comes with a disturbance the film never resolves, and nothing about the comedic frame reassures the audience.

In Eyes Wide Shut, the masks and rituals are attempts to construct a fantasy frame through which the Real of sexual desire becomes consumable. These symbolic structures try to manage desire by giving it form, roles, and choreography. Yet they fail spectacularly. The Real breaks through the fantasy frame, leaving the characters confronted with something they cannot symbolize. The film ultimately turns this confrontation back onto the viewer, exposing how our own fantasy frames operate. This is the gaze of the film, and the title captures it clearly: our eyes may be shut, but the Real remains unavoidable.

Kubrick systematically blocks ego-stabilization. He exposes the subject to the Real.

Restoring Lacanian Gaze in Film Theory

Mulvey’s concept of the male gaze became foundational in film studies because it offered a clear ideological critique: cinema positions viewers within a gendered structure of looking. Its analytical value is undeniable. But its success also had an unintended effect: it overshadowed the usefulness of the Lacanian gaze, which operates on a different register altogether.

Lacan’s gaze is not about point of view, gendered power, or identification. It is not the look of a character, a camera, or a spectator. It is the moment the subject becomes aware of something in the visual field that cannot be mastered, symbolized, or fully understood. It is the intrusion of the Real, an element that does not belong to the symbolic order yet becomes impossible to ignore.

This is where Allen, Hitchcock, and Kubrick illuminate the concept. Allen’s films avoid the gaze entirely because their function is to stabilize the viewer’s fantasy frame. Hitchcock repeatedly produces the gaze by puncturing the fantasy from within, allowing a residue to appear that the narrative cannot domesticate. Kubrick constructs entire worlds in which the gaze saturates the atmosphere, confronting the viewer with something fundamentally inhuman.

These filmmakers show that the Lacanian gaze is not an interpretive lens but an event. It occurs when the image stops serving as a vehicle for meaning and instead becomes a disturbance, no longer affirming the viewer’s symbolic coordinates but exposing their limits. In this sense, the task is not to oppose Mulvey’s gaze with Lacan’s, but to properly restore the Lacanian gaze alongside Mulvey’s productive misunderstanding of it, so that each theory addresses its own register without collapsing one into the other. It draws attention to the moments when cinema exceeds representation altogether and forces the spectator into contact with what their fantasy would otherwise screen out.

Reintroducing the Lacanian gaze into film analysis allows us to see not just how cinema organizes desire, but how it disrupts it. It reveals the moments when the film looks back, when the image refuses to be fully consumed, and when the spectator is confronted with the very thing mainstream entertainment is expected to shield them from: the Real.

Subscribe

I will email you when I post a new article.