Film Review: Peter Hujar’s Day

Watching the film made me aware that interviews convey something beyond information. There is always a layer of atmosphere or impression that sits underneath the words. That dimension of the Real is present throughout the film, and it reminded me how interviews often become more about the person’s presence than about the literal content. About a quarter in, I realized I was no longer listening for information; what they talked about started to feel secondary.

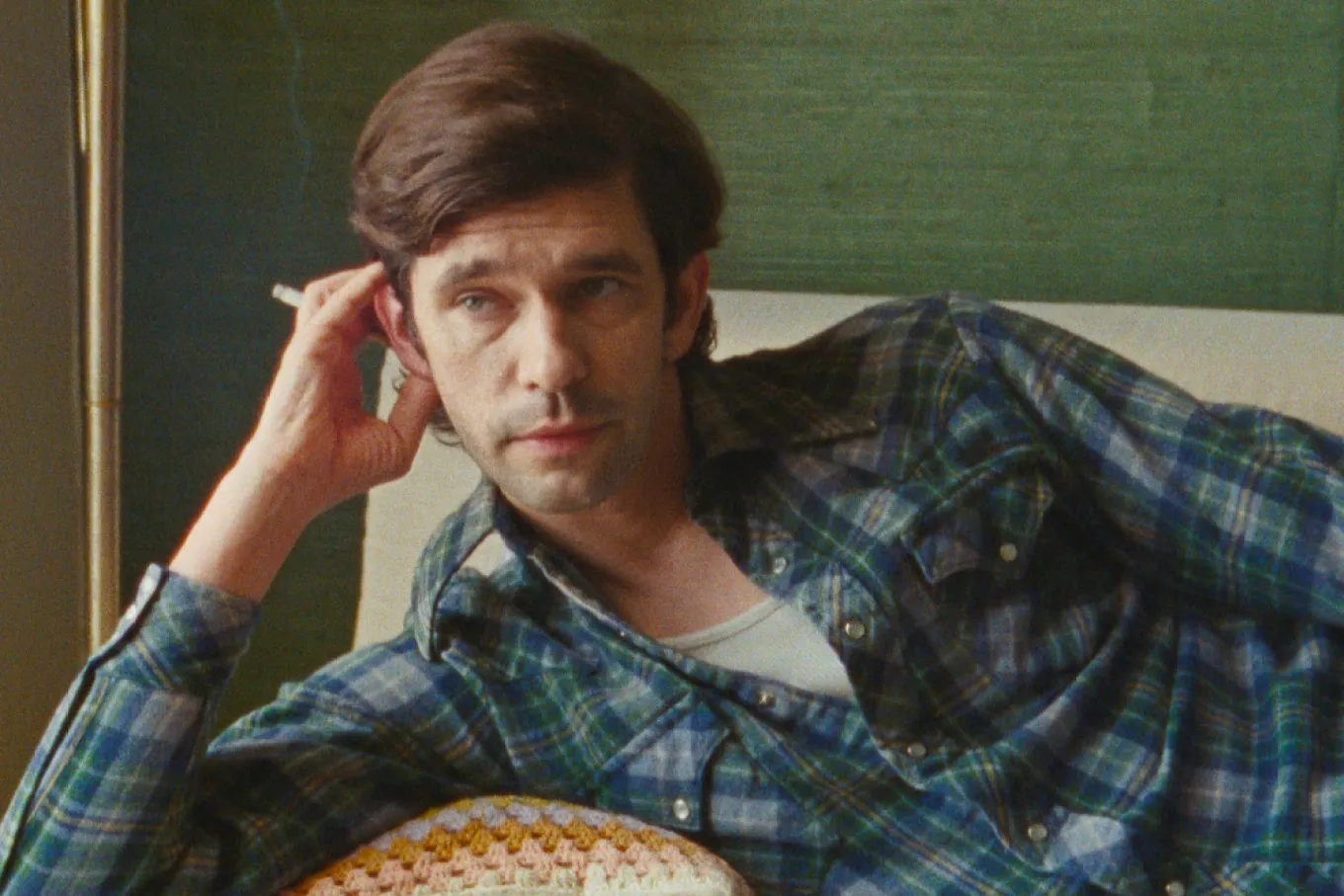

Near the end, Linda Rosenkrantz explains why she asks people to recount the previous day: she often feels like she has done nothing and wants to know how others spend their days. Hujar’s account forces that question into focus. He describes his day with painful granularity. The story feels mundane, but that mundanity becomes the point of the film. He appears to be trying to make sense of the nothing that happened, or perhaps trying to justify it to himself.

Given his status, already a cultural figure, we expect something more eventful. On paper, his day was interesting: a spontaneous photoshoot with Allen Ginsberg, a call from Susan Sontag, even a Vogue editor dropping by. But for him, the Ginsberg shoot was a failure. He couldn’t connect with him and blamed himself. What could easily be recounted as a glamorous New York day becomes, for him, a confrontation with the mundane.

What struck me is that he makes no attempt to turn it into an “exciting story of a celebrated photographer.” He just sits with the banality. That honesty gives the film its force.

The film also shows the pace of life at that time. The shoot with Ginsberg was arranged the same day, over a phone call. That kind of spontaneity is almost unthinkable now. Back then, people made room for things to simply happen, and once they did, there were fewer distractions pulling their attention away.

It reminded me of those twilight moments we all have, when another day passes and we wonder what any of it meant. Something escapes language in those moments; it is the Real, and the lighting and cinematography capture that feeling precisely.

One moment from my own youth came back to me. My friend Neil and I somehow ended up on a beach with our cameras on a cold, windy evening. It was twilight, and the place was empty. I can’t explain why we were there or what the moment was “about.” We hadn’t planned anything. There were no cellphones then, which meant a total disconnection from the world and a deeper level of intimacy that is rare now. Moments like that no longer happen in the same way because the constant pull of our devices breaks the quiet that once allowed them to unfold.

Subscribe

I will email you when I post a new article.