Confession of an Autistic Troll

In my 20s and 30s, I picked fights online every chance I got. Initially, these debates happened over email or chat (since the web didn’t yet exist), but as blogs with comment sections, discussion boards, and eventually Facebook emerged, I enthusiastically engaged in debates there too.

Essentially, I was what we now call a “troll,” relentlessly pointing out every flaw, contradiction, and hypocrisy I encountered. Today, that impulse remains, though I’ve learned to limit confrontations to people who might find the interaction mutually engaging, avoiding strangers.

Reflecting on those years, I think I understand where this drive originated. Even during my childhood, my ideas and questions seemed strange or annoying to everyone around me. Adults and peers often dismissed them as nonsense. From my perspective, it felt like constantly hearing people declare, “1+1 is 3,” and seeing everyone—including teachers—accept it without question. This made me doubt myself, unsure whether I was losing touch with reality or if the world itself was mad.

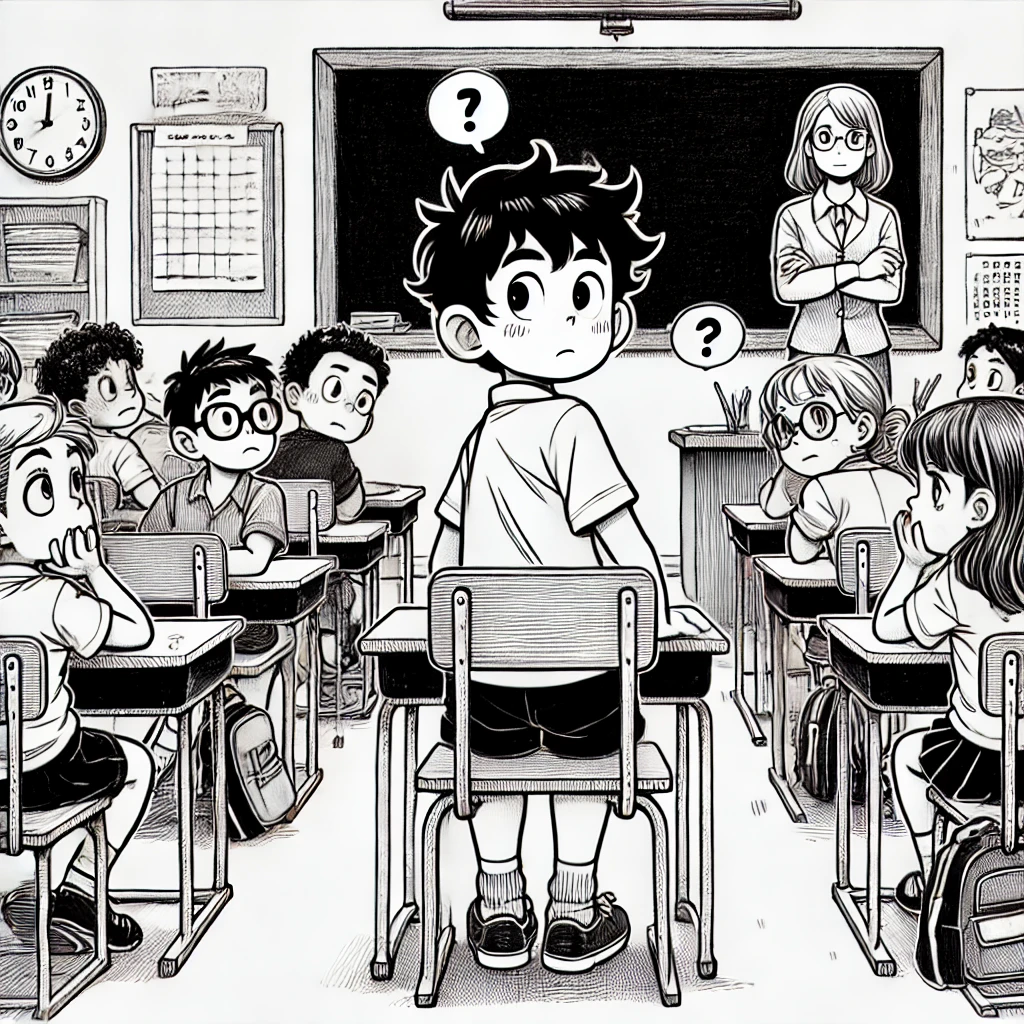

One incident from my fourth-grade math class illustrates this well. My teacher was explaining how rounding numbers works: from x.0 to x.4, you round down, and from x.5 to x.9, you round up. She asked us to raise our hands if we understood. Everyone did—except me. To my mind, including “x.0″ meant continuously rounding down forever. For instance, 5.0 would round down to 4.0, but that, too, would require rounding down because it still meets the same criteria. So, “x.0″ should not be included in the rule, I concluded.

Noticing my skeptical expression, the teacher asked me to speak up. When I explained my objection, she didn’t have an immediate answer but promised to clarify later. The next day, she admitted in front of the class that I was correct. Yet even this rare moment of validation wasn’t rewarding; instead, I sensed resentment from my teacher and irritation from classmates who probably saw me as intentionally disturbing social harmony. In this manner, I was trolling my teacher even in fourth grade.

Experiences like these were frequent throughout my childhood. Over time, I grew bitter, and provoking people and watching them react with outrage or discomfort became satisfying. Repeated rejections led me to assume everyone was intent on interpreting my ideas as nonsense and ignoring me. This perceived injustice became a deep-seated grievance, and trolling became my way of retaliating. Ultimately, though, it was self-destructive behavior, benefiting no one—especially not myself.

Sadly, I knew this even at the time. Changing my behavior just because it didn’t serve my interests felt dishonest and cowardly. The point of living, I felt, should not be survival. Actually, that still holds.

I used to admire statements like, “I disapprove of what you say, but I will defend to the death your right to say it.” It sounded like Voltaire upheld a principle higher than humanity itself—a principle that would remain true even if humans went extinct. In that sense, it’s a religious statement judged by someone above all of us.

So, what changed?

I’m not exactly sure. Something shifted one day. I realized that by upholding such a principle, I was trying to be God myself, the arbiter of universal truth. There is a difference between stating what I think is true, universal or not, and being its judge. The latter means playing God.

After that, insisting on telling everyone what I thought was true felt pointless because no one would benefit from my pretending to be God. Now, I’ll share my thoughts if someone genuinely wants to hear them and seems patient enough, but I no longer have the sense of mission I once did.

Looking back, I don’t regret being a troll. In fact, there was some beauty in that youthful zeal, and I learned a lot from it. Without muddling through that phase, I couldn’t have reached my current state of mind. After all, whatever you are now can only be reached through the exact path you traveled.

Subscribe

I will email you when I post a new article.