Film Review: “Ms. White Light”

Spoiler alert: This is more an analysis than a review. Reader discretion is advised.

Once in a blue moon, I come across an artwork expressing a sentiment I thought nobody else understood. Indeed, “beauty is in the eye of the beholder,” but if there is only one other person in the world who would understand it, is it worth expressing it? From an economic point of view, the answer is obviously no, but from the artist’s point of view, perhaps it is the most meaningful act. This is how I felt about the film Ms. White Light.

Although the film never reveals what makes Lex behave the way she does, it’s consistent with autism. She can instantly connect with the dying even though she cannot converse casually with ordinary people who are clueless about the reality of death. Why would autism allow her to do this?

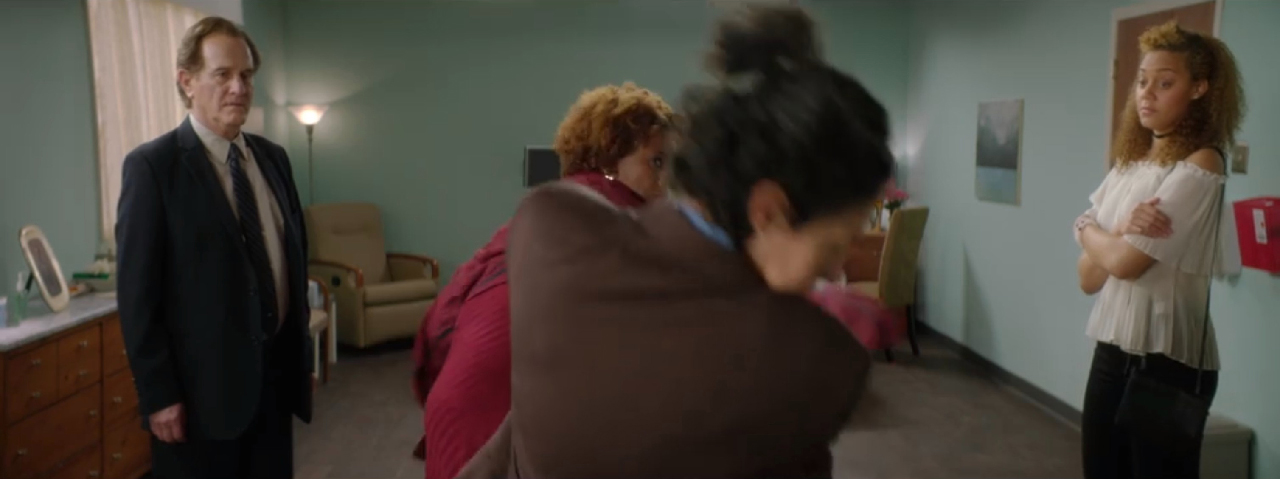

The film opens with Lex talking to a woman on her deathbed. She is intense, sincere, and impassioned, like there is nobody else in the room. As soon as the woman dies, Lex becomes nervous because she has to talk to the relatives of the deceased. She has to look at a stack of cue cards to say the right thing, but even that fails. She gets punched by one of the relatives and walks out of the room with a bloody nose.

Since the relatives have never faced the reality of death, they have the luxury of being in denial of it. Ordinary people talk to each other by avoiding any truth that could hurt each other’s feelings. Lex was punched because she spelled out the truth these relatives had carefully repressed. Because the connections are so distant, we may not realize, but all fears, even social ones, are ultimately a fear of death.

Since the relatives have never faced the reality of death, they have the luxury of being in denial of it. Ordinary people talk to each other by avoiding any truth that could hurt each other’s feelings. Lex was punched because she spelled out the truth these relatives had carefully repressed. Because the connections are so distant, we may not realize, but all fears, even social ones, are ultimately a fear of death.

It’s not so much that autistics cannot have normal conversations but that they can’t see why people have to tiptoe around each other’s feelings. So, they never learn how. All that is required to stop the charade is to confront death. Those who have confronted it can talk to anyone about anything without fear. They do not need you to “filter,” “soften,” or repress any truth. You can tell them exactly what you have in mind. That is what Lex has been doing all her life.

You might think it’s easy to speak exactly what you think if given the opportunity, but can you even think uncensored? The minds of ordinary people are a minefield of repressed thoughts. They intuitively know how to walk around them, so they do not detonate. If anyone gets too close, they react with anger as if it’s his fault the mine is buried there. So, everyone speaks with the fear of stepping on the mines of others. This charade, from an autistic point of view, is almost comical, but the film is told through the neurotypical gaze in which what is funny is the behavior of an autistic person.

The film starts with this insight and raises a deeper question that most autistics have probably never asked.

Even though Lex is confident of her abilities, she comes across a patient, Val, who completely defies her conception of death. She doesn’t seem to have any fear of it. Lex thinks it’s being blocked, repressed, or denied, but she can’t expose it no matter what she tries. Although her business card claims she offers “a brief moment of existential comfort,” Val poses an existential threat to Lex. Being able to remove the fear of death is her justification for existing. She believed that this fear was a universal human condition, yet in Val, she sees a sign that it isn’t universal.

The world of an autistic mind is constructed out of reason. There is no such thing as unconditional love. For someone to see any value in someone else, there must be a reason. If Val has no fear of death, Lex is worthless. Val explains that she hired her, not because she could remove the fear of death, but because she didn’t want to die alone. This doesn’t make sense in Lex’s mind; why would she want a company that offers no value?

Lex is not the only company. Val also hired a handsome, neurotypical psychic named Spencer, who is well-adjusted, tactful, and charming, everything Lex cannot be. He, too, struggles with Val because she doesn’t want to connect with anyone dead; she just wants to connect with him.

The romance between these two characters may seem unrealistic because he is as attractive as a man can be, but Lex has practically no feminine qualities (typical for autistic women because an autistic brain is a male brain according to Simon Baron-Cohen, professor of developmental psychopathology at the University of Cambridge). But autistic relationships run deep; they do not connect at the surface. Spencer, for some reason, is also fascinated by death. He runs towards it, not away from it. The two of them confronting Val’s death is almost like firefighters rushing into the fire. Such deep connections transcend conventional trappings of mating.

The “banter” between them at the hospital cafeteria starts out with an expected conflict between an autistic and a neurotypical, but unlike most autistics trained to feel ashamed of not being able to have small talk, Lex is unapologetic about her disdain for it. Spencer eventually comes to respect her attitude and apologizes. He stops the small talk and dives into the subject that deeply concerns both: Val. Lex does not beat around the bush; she tells him that what he does is “bullshit.” Instead of being offended and walking away, he stays put and delivers one of the best lines in the film: “Yeah, everything is bullshit the minute you pretend that death isn’t fucking terrifying.” Spencer, to Lex’s surprise, turns out to be a neurotypical capable of dropping the charade when he sees a worthy opponent.

The “banter” between them at the hospital cafeteria starts out with an expected conflict between an autistic and a neurotypical, but unlike most autistics trained to feel ashamed of not being able to have small talk, Lex is unapologetic about her disdain for it. Spencer eventually comes to respect her attitude and apologizes. He stops the small talk and dives into the subject that deeply concerns both: Val. Lex does not beat around the bush; she tells him that what he does is “bullshit.” Instead of being offended and walking away, he stays put and delivers one of the best lines in the film: “Yeah, everything is bullshit the minute you pretend that death isn’t fucking terrifying.” Spencer, to Lex’s surprise, turns out to be a neurotypical capable of dropping the charade when he sees a worthy opponent.

Another character who has been transformed by the reality of death is Nora, a teenager who has been neglected by her parents. Before she went into a coma, Lex had successfully removed her fear of death. An experimental drug allowed her to come out of the coma and to spend a few weeks with Lex and her father. She has an unlikely fascination with Bushido, the moral code of Japanese samurai.

Bushido can be described as a lifelong pursuit of overcoming the fear of death. To be a samurai, one must be capable of seeing life with a disinterested gaze, like being able to see a picture of a naked woman as a form of beauty, not as a sexual object. One cannot be attached to it.

Temple Grandin, arguably the most famous autistic, develops humane ways to slaughter cows. It’s not that she does not care about life; she simply isn’t attached to it, which is what allows her to work diligently and compassionately on designing a killing device.

It’s understandable for Nora to be drawn to Lex, who possesses the disinterested gaze on life that Bushido strives for. She wanted to spend the last two weeks of her life with a fellow samurai. Nora, like Spencer, is also capable of straddling the two realities: death and denial. On the way to the hospital to see Val in her last moment, Nora sees Lex resting her head on her father’s shoulder while he holds her tightly. It’s a rare moment where Lex acts like a normal human being. To Nora, whose parents neglect her, it must feel ironic that someone who doesn’t appreciate it gets what Nora has wanted all her life. But she knows she needs to transcend it, as samurai do.

When Nora dies unexpectedly, Lex is visibly angry, probably because she did not get to spend the last moment with her, the moment that is their life’s work. Her father, Gary, doesn’t understand but knows enough not to stop her from leaving the scene of death.

The film is essentially told from the point of view of Gary, a loving, empathetic, neurotypical middle-aged man. What Lex, Spencer, and Nora do is beyond his comprehension. The audience relates to his perspective and curiously observes what unfolds between the three. But, at the end of the film, he disappears. Lex is no longer dressed like her father, and she works with Spencer as a partner.

Perhaps her experience with Val allowed her to embrace the feeling of ambivalence to some degree. She realizes life has meaning beyond reason. She is no longer defensive when the clients question her value. She can see what Spencer contributes to the art of confronting death. She drops the stack of cue cards into the trashcan, which is her final attachment to her father. She manages to eke out a subtle smile as the film ends.

I don’t know what Paul Shoulberg, the writer/director, knows about autism, but in the end, it doesn’t matter because knowing about a disorder, regardless of how well, doesn’t make you an artist. I was blown away by his work.

Subscribe

I will email you when I post a new article.