The Ethics of College Admissions

The fundamental flaw of college admissions is the assumption that the value of human beings can be measured and compared. If I were to ask if it’s possible, most college admissions officers, I’m sure, would say no. This notion is collectively repressed because everyone knows it’s wrong, but they can’t help it, like a fantasy of having an affair.

There is much debate about “fairness” in the college admissions process, but if the value of human life cannot be measured, how could it ever be “fair”? In art, for instance, the idea of fairness does not come into play until we attempt to measure or compare, as in contests, prizes, and museum selections. If you like a particular piece of music, you don’t need to justify it, even if nobody else does. To put it another way, a debate about “fairness” implies measurement.

So, what exactly are colleges measuring? Now that standardized tests are out of fashion, more weight is put on essays, interviews, and even videos. The problem from an ethical point of view is the pretense of objectivity. If it’s subjective, by whose subjective standards are we measuring the value of these teenagers?

I have never met anyone who claimed to be a poor judge of people. One of the reasons is that there is no way to account for it. It reminds me of the old days of advertising when measuring the performance of ads was impossible. Back then, art directors and copywriters had a lot of fun and thought they were geniuses. With the advent of interactive advertising, the party ended. Now, advertisers demand performance metrics and hold creatives accountable.

But this isn’t possible with college admissions. In general, the goal is some vague idea of “success,” so they look for students who are self-motivated, ambitious, and show “leadership” qualities. They know they can’t measure these qualities, so they rely on evaluators’ subjective opinions. Like everyone else, these evaluators believe they are great judges of character and believe they can detect authenticity.

On the flip side are the writers and editors of college essays who believe they know exactly what college admissions officers are looking for and believe they are talented enough to fool the evaluators. Personally, I would put more money on the latter since the stakes are higher for them. After all, they are measured to some degree by how many students they send to elite colleges.

But either way, there is no real accounting. So, they can believe they are geniuses like those Madison Avenue ad men did. For instance, take Elizabeth Holmes, the disgraced founder of Theranos. She still checks all the boxes: smart, confident, self-motivated, ambitious, and with leadership qualities. Hitler did too. You might say, “Well, you also have to evaluate moral character.” Firstly, if the investors who poured millions into her venture thought her moral character was not only sound but admirable, what makes you think college admissions officers can do better? After all, Hitler became powerful mainly for his moral character, as evaluated by the majority of the German people at the time. Evil, we discovered, is quite banal. Hannah Arendt found Adolph Eichmann to be “terrifyingly normal.” If he was a student applying to Harvard, I don’t think anyone would have detected any warning signs.

Another buzzword in college admissions is “diversity,” which is being used to justify rejecting qualified students, particularly Asian students. The irony here is that they are selective about what kind of diversity they want, and by “they,” I mean predominantly white administrators. For instance, they clearly do not want diversity of intelligence. Elite colleges are a homogeneous environment of highly intelligent students, which is part of the reason Hillary Clinton unexpectedly lost to Donald Trump. The political elites are completely out of touch with ordinary Americans. In this regard, Ivy League colleges would do well by accepting C students, but they wouldn’t. They only pay lip service to the buzzword.

The real danger and the ethical problem here is the arrogance of these evaluators who think they can measure and compare human beings.

I was born and grew up in Japan until my junior year in high school. Their standards for evaluating students are objective for the most part. Exams trump everything else. It was a thoroughly dehumanizing experience, but at least there was no pretense. We knew what they were measuring: our test-taking abilities.

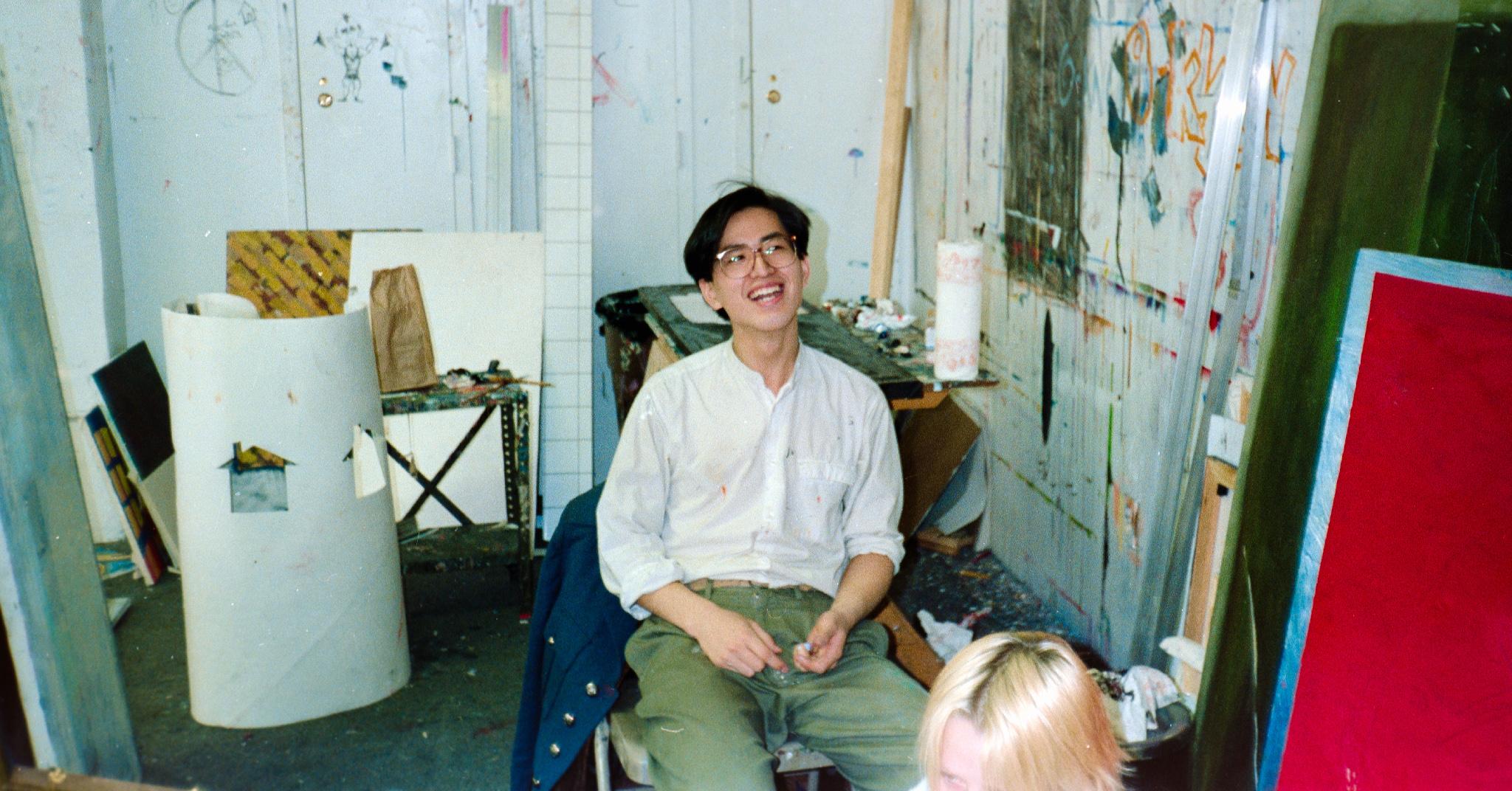

For the last two years of high school, I lived with an American host family in a suburb of Los Angeles. For college, I did not want to subject myself to any type of measurement, so I moved to New York to study fine arts at the School of Visual Arts (SVA). “Anything competitive cannot be of any substance,” I wrote in my notebook at the time, because I hated my own competitive drive.

In high school, I was ignored and bullied by the suburban kids because I couldn’t speak English, but at SVA, three people took me under their wings to introduce me to their friends, give me lessons on New York culture, teach me how to dress, invite me to their parties, and hang out with me day and night for four years. Jordan is a native New Yorker who knew everything hip and cool around the city and dragged me into every trendy nightclub. Jimmy was a graffiti artist from the Bronx with a million friends who decided that I should be his roommate. Brenda was my next-door neighbor at the dorm who introduced me to many girls, including my first wife. To this day, I’m not sure what was in it for them to take me on as their personal projects. My English was still poor, and now that I speak fluently, I know how awkward and tiring it is to listen to someone with broken English.

One night at the school studio, spontaneously, we sat around in a circle and recounted our high school horror stories. It was clear that most of us were bullied or ignored in high school. We were weirdos who couldn’t fit any mold. To be measured and compared, you first have to fit some type of mold. This meant that we couldn’t understand the realities of those who did. It is no wonder we were ignored; we were living in different realities.

In a way, we were also selected by the admissions process of conventional colleges; we were products of rejecting it. We didn’t want to be superior to anyone; we wanted to be singular. We saw through the collective repression and the delusional assumption that human life can be measured. Like in the film The Matrix, we wanted to take the red pill so we could live in the sewer system. We’d rather be true to ourselves than be happy. It’s a peculiar mentality you find among artists.

From this point of view, perhaps the college admissions process works unintentionally, but there could be some in-between solutions. The students who pursue the path of singularity are a tiny minority, which is unfortunate. It doesn’t have to be so. More colleges could commit to not measuring or comparing their students, accept them randomly if there are too many applicants, and drop the pretense that these teenagers can somehow be compared.

One of the top regrets of the dying is, “I wish I’d had the courage to live a life true to myself, not the life others expected of me.” When you pursue the path of singularity, you can’t expect anything because you do not know where the destination is. Even if scoring 1,600 on the SAT is your personal goal, it is a standard set by “others.” Without the expectations of others, that goal would be meaningless. The path of superiority is necessarily paved by others. We as a society have an ethical obligation to make our children aware of this, so that they see an alternative to being at the mercy of delusional, self-aggrandizing judges who are naive enough to believe that they can see through the depth of any humans and measure their worth.

Subscribe

I will email you when I post a new article.