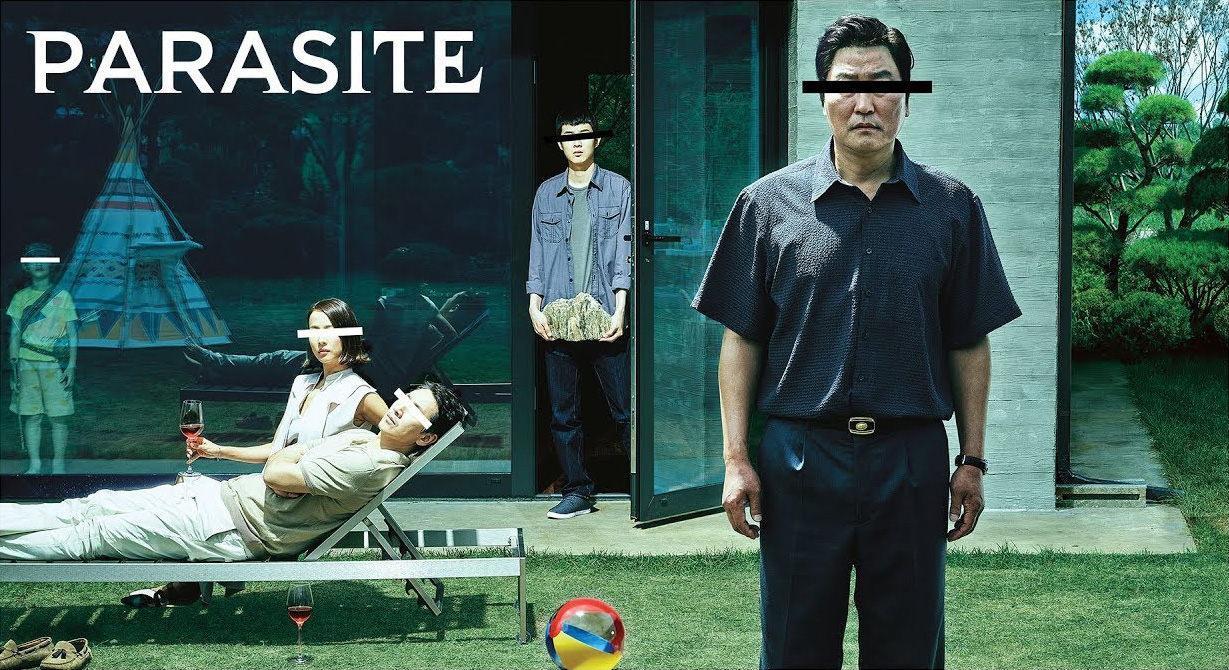

Film Review: “Parasite”

With all the great things coming out of South Korea these days, I assumed Parasite too must be a great film, especially since everyone has been raving about it. This is one of those moments where I feel like I’m hallucinating; Is it just me who thought the film sucked?

I read a bunch of reviews, but they just go on about how great it is and provide no insight into why. For the most part, they only describe the plot and how they liked the cinematic style and metaphors. They all talk about the “social commentary,” like the idea of class disparity and social inequality, but do not explain in what way the film succeeds in enlightening us about our society.

Is it Shakespearean or Hitchcockian as some claim? No. I’ll tell you why. Parasite has no psychological depth. In fact, it is so shallow that it insults me as an audience.

The poor family who scams their way into the inner life of the rich is quite creative, skillful, and resourceful, and they are so ambitious that they are willing to screw anyone over along the way, like the friend who originally gave Kevin the opportunity, the original housekeeper, and the chauffeur. This type of resourcefulness and ambition is what makes one successful in capitalism. It is too unrealistic for them to be so poor, especially in a modern, democratic society like South Korea.

The class division and inequality persist in a capitalist society largely because each class is a culture that must be mastered in order to become a member, and because one needs access to the upper class in order to master it, the poor are rarely given those exclusive opportunities. Some parents stretch their income to send their kids to private schools just for that type of access, not only for their kids but also for themselves.

Yet in the film, all the members of the Kim family somehow already know the culture of the rich well enough to be able to manipulate them. That is too naive and unrealistic. If the film is to be a social commentary about class division, its understanding of it cannot be so superficial. From this point of view, the film is certainly not Shakespearean.

You might argue that a film doesn’t have to be realistic. True; for something to be real, it doesn’t have to be realistic. For instance, pretty much all science fiction movies are unrealistic. The fact that everyone is speaking English in Star Wars is absurd if you were concerned about being realistic. The same is true for Picasso’s paintings. Just because we cannot see the backside of the cereal box on the table, doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist. In this sense, what is “real” can certainly encompass the reality beyond the limitations of our eyes and their particular 3-dimensional projection. Yet, in both of these examples, what is at stake is something real.

According to the reviews I read, the director is apparently famous for his use of metaphors. One of the characters in Parasite talks about metaphor too. But, I’m not sure if the director understands what a metaphor is.

What is a metaphor? It’s a logical or structural parallel. There are countless worlds that are self-consistent within each. Take Terry Gilliam’s Brazil, for instance. It’s a completely made-up world that only has some vague resemblance to ours, but it has internal consistency which allows many aspects of it to function as metaphors for the things and phenomena in our world. We can painfully relate to the main character’s sense of alienation working in a bureaucratic system. This sense is enhanced, made even more real, because the metaphor allows the filmmaker to exaggerate the aspects that bring out the sense of alienation while eliminating the aspects that do not contribute to it. This is hard to achieve if the film were to conform strictly to our reality. All that is required for a metaphor to work is the structural consistency within each of the two worlds. You do not find that in Parasite. There are no salient metaphors that can draw parallels with our world because the film has no internal consistency. We only find vague allusions.

The same problem afflicts the inner worlds of the characters in the film. Each of our emotional life has internal consistency which allows us to understand each other. I understand my friend as a certain type of person, and even if I cannot articulate it logically, there is certain cohesion in the way he thinks and behaves. When I hear someone describe something he did, I might say something like, “Oh, that is so Eric.”

Parasite’s understanding of the human psyche is so superficial that we do not understand what motivates these characters to do anything. One moment they are supremely confident at what they do, and the next moment they are helpless. One moment they are coherent, and the next moment they are psychotic.

The theme of the film is similar to that of The Grifters, but Parasite does not show us how one becomes so cunning or what is hidden behind those sociopathic behaviors. Instead, the motives are left unresolved, like why Mr. Kim had to kill Mr. Park. Ostensibly, it’s because the latter humiliated the former for his body odor, but why that would have to lead to murder is never explained or shown. It’s like a cop-out plot where a series of strange behaviors and events are revealed in the end as a dream. It gives us no insight into the human psyche that drives one to such extreme behavior. From that point of view, Parasite is not Hitchcockian either.

There are also many logical inconsistencies that make the whole movie too unrealistic to be a salient critique of our society. For instance, people who are as street smart as the Kims are supposed to be, should know that the Parks may come back from the camping trip because of the rainstorm. Who didn’t see that coming? They had outlandish solutions to everything at the beginning of the movie, but after they escaped from the former housekeeper and her psychotic husband, they suddenly had no idea what to do. Given how confidently they handled their jobs with the Parks, why couldn’t they have just fessed up, run away, and found some other opportunity? Why become so desperate suddenly?

Towards the end, if Mr. Kim was able to step outside while the new family was away, why couldn’t he just find a computer in the house and email his son, or simply mail it? Surely, he could find some money in the house, or something valuable to sell, in order to buy some stamps. Sending morse code may make sense for the psychotic man who had been living in the nuclear shelter for years, but Mr. Kim is not supposed to be psychotic.

None of these behaviors give us any insight into the inner workings of these characters. They are just symptoms without any clues into the causes because the film itself has no understanding of its characters. Like the Postmodernism Generator that automatically produces a close facsimile of postmodernist writing, Parasite randomly strings together all the stylistic gimmicks of hip independent films. It’s like a poem made up of beautiful words and perfect rhymes that ultimately says nothing, teaches us nothing, and asks us nothing. It’s just an amusement for the gullible Hollywood audience like the Parks.

If this were a small independent film, I wouldn’t bother writing a scathing review of it, but given that this was celebrated in Hollywood as one of the best films, I have to lament the pathetic state of Hollywood and its film critics. This is more a critique of the depressing state of the industry than it is of the film.

Subscribe

I will email you when I post a new article.