Why We Shouldn’t Vote to Win

Vote to win or vote for what you believe in? That is the question we can now revisit.

People who voted for third party candidates were harshly criticized and ridiculed. Sanders’ supporters were mocked and dismissed as “Bernie bros” because he was regarded at the time as not electable.

After analyzing Clinton’s surprise defeat, now we know that Clinton was the wrong candidate to be fighting against Trump because the anti-establishment sentiment was the predominant drive in this election, and Clinton is the epitome of the establishment.

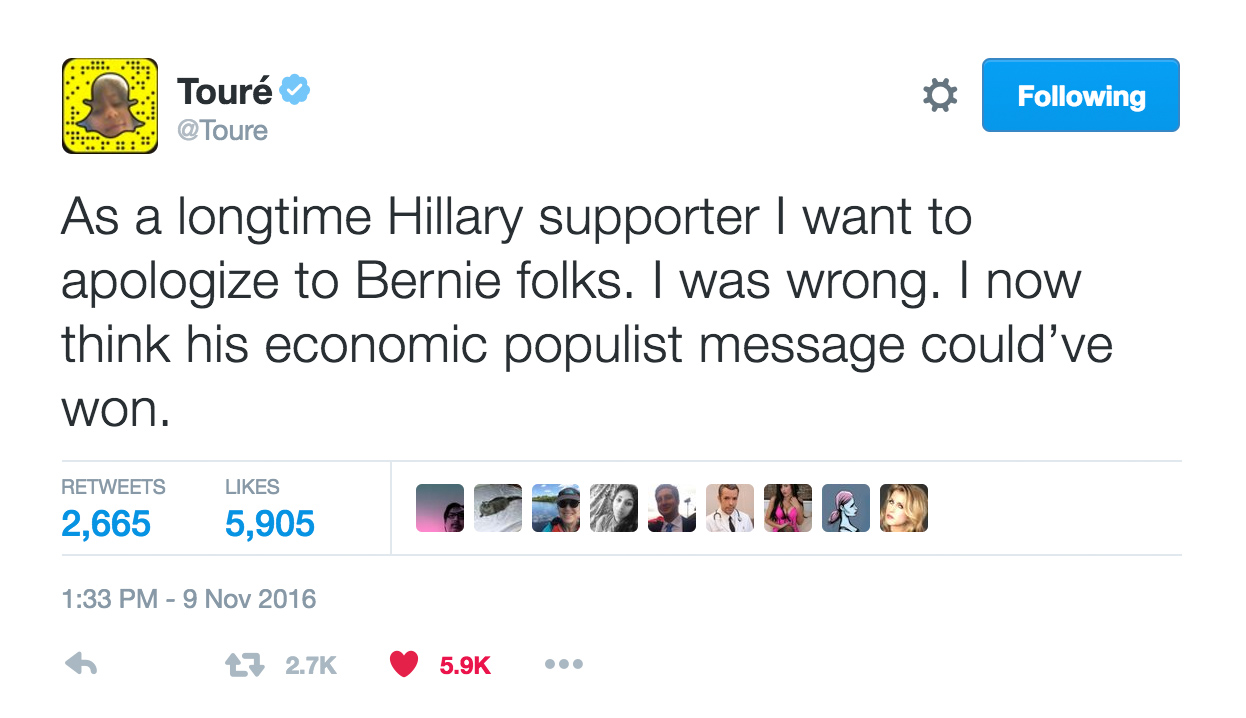

If voting to win is morally superior, then those Clinton voters who criticized others for not voting for the winnable candidate deserve all the criticism aimed at them from Sanders supporters. It is not fair to morally accuse someone when you think you are right and then refuse to listen to accusations when you are wrong. You cannot conveniently dismiss the accusations now by saying “Let’s stop blaming each other.” You are making them suffer the consequences of your mistake. The least you can do is to apologize.

This is one of the problems with voting to win. It distorts the will of the people by forcing consensus and suppressing dissent based on whatever dominant speculation or theory we have at any given moment. And if anyone is powerful enough, s/he can manufacture this consent. Voting to win distorts and degrades democracy.

Even if Clinton had won (she did in the popular vote), it would have been clear from the surprising strength of Trump that an anti-establishment candidate was what the majority of people were looking for. Many are now accusing Trump of stealing the election because Clinton won the popular vote, but she herself stole it from Sanders.

During the primary, the basis of the argument that all Democrats should vote for Clinton was not based on hard facts (in fact the data suggested otherwise) but simply on the general consensus that she was the more electable one.

Now the general consensus says we were wrong about what was motivating the majority of voters. Given the same moral standard the accusers of Sanders supporters used, we can now say they were wrong and that they used their presumed moral superiority to mislead the Democrats.

To be clear, I’m not saying Clinton supporters were wrong to vote for Clinton. I respect their choice even though we now know she was not the right candidate to win. This is because I do not believe in vote-to-win. From my point of view, those who truly believed in Clinton did the right thing by voting for her. But they cannot conveniently switch their moral position from vote-to-win to vote-for-who-you-believe-in after the fact in order to deflect accusations. If vote-to-win is your moral position, then don’t be a hypocrite; you were wrong by your own standard.

Many Clinton supporters also expressed their moral outrage towards those who saw this election as “the lesser of two evils,” because they were blind to what was driving the anti-establishment sentiment. In their eyes, there was no question. To them, only bigots would choose Trump. In this election, non-voters too had legitimate reasons behind their choice.

Furthermore, when we make moral accusations, it makes reconciliation and healing much harder because admitting mistakes is much harder for moral transgressions, which in turn means we are unlikely to receive any apologies. The accused will have to hold some degree of their resentment forever, so it keeps on dividing us every election.

You can persuade others to your view but moral superiority should not be used to back up your own political position or to criticize those of others. Just state what your position is and what you believe in, and leave it at that. If we want democracy to flourish, we should vote for whoever we believe in and respect the choices others make.

Subscribe

I will email you when I post a new article.